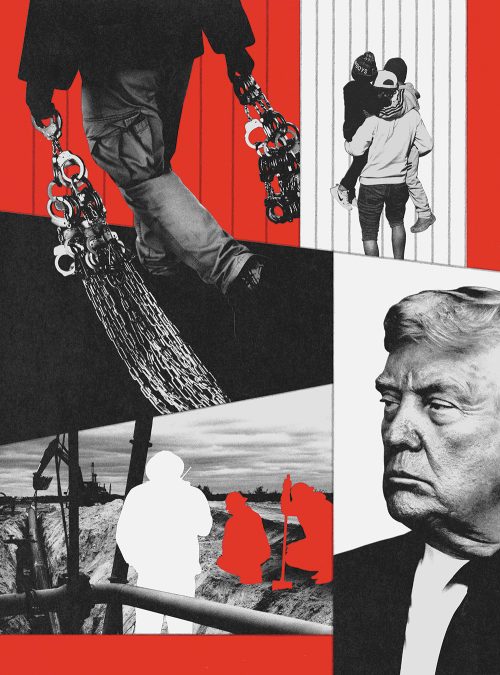

- The Forever Wars Have Come Homeby Conor Lynch on October 1, 2025

After President Donald Trump’s reckless bombing of three nuclear facilities in Iran last June, commentators were quick to draw parallels with George W. Bush’s calamitous invasion of Iraq in 2003, once described by Trump as possibly “the worst decision” in presidential history. After initially capturing the GOP a decade ago by railing against neoconservatives and

- Trump Is Trying to Bludgeon South Korea Into Submissionby Kap Seol on October 1, 2025

On September 4, US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents rounded up 434 South Korean nationals who were working at the construction site of an electric vehicle (EV) battery plant in Georgia. The plant was jointly built by two South Korean companies, Hyundai Motor Group and LG Energy Solution. The biggest single ICE raid to

- Terrorist with white flag tries posing as a hostageby Batya Jerenberg on October 1, 2025

The IDF suspects he might have been a decoy to lure soldiers into a trap. The post Terrorist with white flag tries posing as a hostage appeared first on World Israel News.

- Mexican President Sheinbaum’s Triumphant Year Oneby Kurt Hackbarth on October 1, 2025

On September 15, Claudia Sheinbaum — the first woman president in Mexico’s history — stepped onto the balcony of the National Palace to perform the ritual grito, or cry of independence. In keeping with her government’s drive to recognize overlooked female figures in Mexican history, she included among the familiar pantheon of independence heroes names

- Gaza flotilla crew rejects Italian calls to turn back, Israeli navy says ‘We will stop you’by Miriam Metzinger on October 1, 2025

The flotilla is nearing the "critical zone," and Israel's navy has issued a stark warning that it will deal with violations against the blockade, which is permitted under international law. The post Gaza flotilla crew rejects Italian calls to turn back, Israeli navy says ‘We will stop you’ appeared first on World Israel News.

- Why Class Matters as Much as Everby Vivek Chibber on October 1, 2025

Utilizing class analysis is the bread and butter of socialist politics. But understanding how classes are shaped and reproduced has changed over time. In a recent episode of the Jacobin Radio podcast Confronting Capitalism, Vivek Chibber breaks down how the Marxist tradition has theorized class, the difference between a class in itself and a class

- Gaza and the Economy of Genocideby Matan Kaminer on October 1, 2025

The world watches in shame and fear as Israel invades Gaza City, bringing its genocidal campaign against the Palestinians to a new level of horror. Public opinion throughout the world, including the United States, has long since turned against Israel’s aggression. The highest organs of international governance have all issued calls to cease and desist.

- Israel’s positions reflected in U.S. peace plan after Netanyahu-Trump talksby Batya Jerenberg on October 1, 2025

Two key achievements were no full IDF withdrawal from the Strip and Hamas’ complete disarmament. The post Israel’s positions reflected in U.S. peace plan after Netanyahu-Trump talks appeared first on World Israel News.

- Did Reebok demand removal of its logo from Israeli team jerseys?by Lauren Marcus on October 1, 2025

The Israeli Football Association says Reebok reversed course only after legal threats. The post Did Reebok demand removal of its logo from Israeli team jerseys? appeared first on World Israel News.

- Trump administration cracks down on synagogue protestersby David Rosenberg on October 1, 2025

Justice Department files lawsuit against anti-Israel activists who targeted New Jersey synagogue last year to protest real estate fair featuring properties in Israel. The post Trump administration cracks down on synagogue protesters appeared first on World Israel News.

- WATCH: Oct. 7th survivor walks down the aisle after overcoming devastating injuriesby Yossi Licht on October 1, 2025

A year after surviving multiple wounds, a coma, and the horrors of October 7, Michelle Rukovitzin defied all odds by walking to her wedding canopy, hand in hand with the fiancé who never left her side. The post WATCH: Oct. 7th survivor walks down the aisle after overcoming devastating injuries appeared first on World Israel News.

- Did Israel just stop Russian influence in the Middle East?by Yossi Licht on October 1, 2025

Israel's willingness to act unilaterally upends predictable regional bargaining and weakens the presumption that Moscow calls many of the shots. The post Did Israel just stop Russian influence in the Middle East? appeared first on World Israel News.

- Palestinian UN representative blames Israel for ‘famine’ in Gaza from his luxury Manhattan apartmentby Yossi Licht on October 1, 2025

Bamya has used his position to speak about deprivation and hunger in Gaza—blaming the conditions on Israel—while spending his time far away from the people he claims to represent. The post Palestinian UN representative blames Israel for ‘famine’ in Gaza from his luxury Manhattan apartment appeared first on World Israel News.

- We Desperately Need Maximum Wage Lawsby Celeste Pepitone-Nahas on October 1, 2025

In the first year of President Donald Trump’s second term, the power of the extremely wealthy over public policy has never been more evident. As Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) has asserted, “Trump has . . . said it loudly and clearly: we are a government of billionaires.” The troubling extent to which we are ruled

- IDF probe: Nir Am saved by local squad, army and police supportby Lauren Marcus on October 1, 2025

Nir Am’s local security squad and a nearby IDF unit prevented terrorists from infiltrating the kibbutz. The post IDF probe: Nir Am saved by local squad, army and police support appeared first on World Israel News.

- WATCH: ‘We’re hooked up for life,’ says Huckabee on Israel-US relationsby Yossi Licht on October 1, 2025

US Ambassador Mike Huckabee brushed off talk of a rift with Israel, joking that the alliance is like a long marriage—too late for divorce, and the alimony would be unbearable. The post WATCH: ‘We’re hooked up for life,’ says Huckabee on Israel-US relations appeared first on World Israel News.

- Maj. Gen. (res.) David Zini approved as director of Shin Betby Yossi Licht on October 1, 2025

Zini, who is Orthodox, has 11 children and comes from a family of rabbis of Algerian descent. The post Maj. Gen. (res.) David Zini approved as director of Shin Bet appeared first on World Israel News.

- Israel thwarts Palestinian attempt to pave over biblical city of Gibeonby Yossi Licht on October 1, 2025

Mentioned repeatedly in the Book of Joshua, it is where Joshua made a covenant with the Gibeonites and the site of the famed battle in which 'the sun stood still at Gibeon, and the moon in the valley of Ayalon.' The post Israel thwarts Palestinian attempt to pave over biblical city of Gibeon appeared first on World Israel News.

- Iran bombing soon? Dozens of of U.S. jets deployed to Qatarby Lauren Marcus on October 1, 2025

A sudden surge of U.S. refueling aircraft in Qatar is fueling speculation of new strikes on Iran. The post Iran bombing soon? Dozens of of U.S. jets deployed to Qatar appeared first on World Israel News.

- WATCH: Recap of monumental meeting between Netanyahu and Trumpby Yossi Licht on October 1, 2025

President Trump and Prime Minister Netanyahu met again at the White House to advance a Gaza peace plan aimed at securing the release of all remaining hostages and permanently eliminating Hamas as a threat to Israel. The post WATCH: Recap of monumental meeting between Netanyahu and Trump appeared first on World Israel News.

- US begins deporting hundreds of Iranians after rare deal with Tehranby Yossi Licht on October 1, 2025

Some of the Iranians had volunteered to leave after being in detention centers for months, and some had not. The post US begins deporting hundreds of Iranians after rare deal with Tehran appeared first on World Israel News.

- Two Israeli men arrested for spying on IDF bases for Iranby David Rosenberg on October 1, 2025

Two Israeli Jewish men from the central Israeli city of Holon arrested for allegedly work on behalf of Iranian spy agencies. The post Two Israeli men arrested for spying on IDF bases for Iran appeared first on World Israel News.

- Priests of History: How Christians Should View the Past in a Secular Age by James Diddams on October 1, 2025

In the year 1989, I was an elementary school student in Russia. I may have been atheist or perhaps an agnostic, but in either case I lived in a country where God’s name was not mentioned in polite company. Meanwhile, history ended without my knowledge. Or, at least, so proclaimed Francis Fukuyama in his legendary essay, “The End of History,” which he subsequently expanded into a book-length treatise in 1992. By then, I was a newly arrived immigrant in Israel, and history seemed very much alive. Fukuyama’s original proclamation was a response to the Velvet Revolutions that toppled Communist dictators all over Europe and ultimately led to the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, mere months after my own family left Russia for Israel. If liberal democracies rule the day, his logic went, then ideologies like fascism, communism, and authoritarianism will lose their appeal. Mankind will enter a new age of peace and therefore history, in the sense of a dialectical progression towards the ultimate meaning of politics as the “master science,” whose “end is the human good,” will be concluded.1 Alas, this remarkably optimistic prediction did not come true, as we now know with over three decades of hindsight. But an even more ignorant and apathetic view of history has arrived. To be precise, we are living in what historian Sarah Irving-Stonebraker calls an “Ahistoric Age” in her recent book, The Priests of History: Stewarding the Past in an Ahistoric Age. How Christians see their past and present and future has always been connected to how they think of God. For Christians, put simply, God is the author of history, and this changes everything. Except, in our Ahistoric Age, Christians alongside everyone else seem to have forgotten this. Irving-Stonebraker contends that while the roots of the Ahistoric Age existed earlier (cue Fukuyama), it demonstrably took off around 2010, right alongside the ubiquitous iPhone. She identifies five key characteristics of this age: “1. We believe that the past is merely a source of shame and oppression from which we must free ourselves. 2. We no longer think of ourselves as part of historical communities. 3. We are increasingly ignorant of history. 4. We do not believe history has a narrative or a purpose. 5. We are unable to reason well and disagree peaceably about the ethical complexities of the past—that is, the coexistence of good and evil in the same historical figure or episode.” Irving-Stonebraker brings up G. K. Chesterton’s fence analogy as characteristic of the Ahistoric Age. Someone who comes across a fence in an unexpected place might stop first and think about the possible purpose of the fence: Why was this fence erected? Surely not for nothing. Such would be a responsible historical reaction. But, as products of the Ahistoric Age, we are inclined to just take out the fence without giving it another thought. So too goes our attitude towards our heritage; having developed over numerous generations, we should not presume the wisdom of our inherited customs can be discarded so easily. But it’s not just that the hypothetical fence seems to be lacking in purpose in our landscape. Rather, we’ve lived through a number of scandals around memorials and public statues over the past decade, and in each case, the argument for removal, while contending to draw on history (the statue as an object of commemoration of a historic person or event) is stemming, rather, from ahistoric sentiments, Irving-Stonebraker contends. If the person or event being commemorated seems offensive to people today, then it must be removed. But such is not a historical perspective—and it is certainly not a Christian way of viewing the past. What is the responsibility towards the past specifically of Christians living in this Ahistoric Age? Irving-Stonebraker feels passionately that all believers must learn their history and understand their connection to previous believers. But we must do more than that: “We must understand how we can engage in the practice of history. In this book, I am arguing from a biblical position that all Christians are called upon to tend and keep history—to be priests of history. This does not necessarily mean I expect all of us to roll up our sleeves and dig into the archives or write professional or scholarly history. But it does mean all Christians can engage with history in our daily lives and pass down our heritage, especially through our intellectual and spiritual formation and discipleship.” After explaining the genesis of our Ahistoric Age in Part I, Part II explains “Why We Need History,” showing how a more accurate view of the past enables us to recognize the past without being beholden to it. Instead of attacking statues, for instance, having a more nuanced view of the past can help us think about all persons of the past as God’s creations, whose stories matter because they too are part of the larger story God is writing through us all. Finally, Part III, “How History Can Help Us,” offers more practical takeaways in thinking historically about our own lives, our connection to our past (national, churchly, family-related), and how to think prayerfully about our future. Throughout, Irving-Stonebraker brings up concrete historical examples from her areas of expertise and best familiarity—British and Australian history. As an ancient historian, I encountered a number of figures for the first time, but Irving-Stonebraker’s orientation of the reader to them required no previous knowledge to understand her use of these examples. In fact, perhaps the obscurity of some of these examples only further proves her point that as Christians, we see the less-known figures of the historical past differently. By commissioning all of us as “priests of history,” Irving-Stonebraker emphasizes the significance and weight of our task as Christians, people living in one particular time, but acutely aware of our connection to other Christians and the church across time. History is an integral discipline for the health of the church, because the very claims on which the church rests are intensely historical. But there is another essential component to this book: for Irving-Stonebraker, this is no mere theological exercise. This book is a passion project that isn’t just a reflection on what history should mean to every believer—although it certainly is that, and that alone would make it worth reading. Still, the additional dimension driving the book is deeply personal, and it makes it all the more compelling. Like myself, Irving-Stonebraker is an adult convert to Christianity. Originally an atheist academic, she came to realize that the claims of the faith are true. She found true joy and purpose in her academic work as a historian in the process. In other words, while this was obviously not the reason for her conversion, becoming a Christian ultimately made her a better historian. In a world where Christians too often are asked to keep their faith private, this is a key point. When historian George Marsden first published The Outrageous Idea of Christian Scholarship in 1997, his premise was as contentious as the title makes it sound (I am still a little bit amazed that Oxford University Press published it!). Can Christians be good historians, scientists, artists and writers? Yes, of course. But can they be good historians, scientists, artists, or writers as Christians? Can they combine their professional persona with their faith and retain their academic credibility? Some in the secular academy were decidedly skeptical, and the burden fell on Christians to show their case. Historians like Marsden, who was lauded for his scholarship by secular and Christian institutions alike, were excellent case studies of this phenomenon in action. But it is time for a new generation of Christian historians and other practitioners to pick up the baton now. This Ahistoric Age of ours offers its challenges to Christians, to historians, and to Christian historians. And yet, it also offers opportunities. Our work as researchers matters in a cosmic sense, as strange as it is to wrap our minds around this concept. It is by practicing our love for our historical subjects in our research, in our churches, in our homes, and in our friendships and in various other relationships, that we will not only steward history well, but will follow God’s call to delight in this world he has made—in our research, too. This entire world is God’s temple. And we are his priests.

- Inside the many, many Labour Party Conferences taking place in Liverpoolby Seth Thévoz on September 30, 2025

So disjointed is Labour’s annual meet, the messaging differs from room to room. Attendees agree only on fear of Reform

- Democrats Are Already “Moderate.” It’s Not Working.by Waleed Shahid on September 30, 2025

Every election cycle produces the new miracle cure: Democrats should moderate. Ezra Klein has framed it as choosing power over purity — living with candidates who diverge from standard progressive preferences on abortion, immigration, or trans rights, the way Barack Obama once opposed same-sex marriage to win a national coalition. Matt Yglesias argues that economic

- Gustavo Petro Isn’t Afraid of Donald Trumpby Cruz Bonlarron Martínez on September 30, 2025

The US Department of State published a tweet on Friday night stating its plans to revoke the visa of Colombian president Gustavo Petro due to his “reckless and incendiary actions” on his visit to New York City during the United Nations General Assembly. The actions in question were accompanying Pink Floyd singer Roger Waters to

- Sylvan Esso on Why They Pulled Their Music From Spotifyby Amelia Meath on September 30, 2025

At a time when most musicians feel trapped by the streaming economy’s brutally extractive logic, Amelia Meath and Nick Sanborn of the band Sylvan Esso decided to do something at once radical and surprisingly simple: they’ve taken their music off Spotify. The indie electronic duo, whose iridescent synth-pop has garnered a loyal listener base and

- Event: Economic Populism and the Future of the Rust Beltby Editors on September 30, 2025

Join us tonight at 7 p.m. ET for the launch of a major new study on working-class politics in the Rust Belt, produced by the Center for Working-Class Politics and Jacobin in collaboration with the Labor Institute, Rutgers University’s Labor Education Action Research Network (LEARN), and YouGov. The study surveyed 3,000 voters across Ohio, Pennsylvania,

- The US Cheered On Suharto’s Massacres in Indonesiaby Derek Ide on September 30, 2025

Recent scenes from Indonesia have gripped international headlines. Massive youth protests provoked by economic austerity and parliamentary privileges erupted across the country. Yet with rare exceptions such as these protests, the archipelago nation of nearly 300 million people tends to be a distant consideration, even for much of the international left. This was not always

- In Indonesia, Popular Memory Fights Against Official Amnesiaby Michael G. Vann on September 30, 2025

Behind a low wall on a traffic-choked stretch of Denpasar’s east side, a small courtyard insists that Bali’s famous “paradise” has a history. And that history is troubled. On a brick wall is a simple injunction — “Forgive but never forget” — and in the center stands a white bust of a schoolteacher, I Gusti

- Rocky IV: The Quintessential Cold War Sports Movie at 40by James Diddams on September 30, 2025

“Two worlds collide, rival nations. It’s a primitive clash venting years of frustrations…Is it East versus West or man against man?” Thus begins Burning Heart, one of the iconic songs of Rocky IV. This autumn marks the fortieth anniversary of Sylvester Stallone’s Cold War boxing epic, a film that captures one of the elemental aspects of the Cold War. The film captures the clash between a society of free individuals versus a totalitarian regime where human beings are just expendable tools. For those who do not recall, Sylvester Stallone created the Rocky franchise by writing, directing, and acting in the original eponymous movie in 1976. Stallone’s bio is a great American story in and of itself: a young actor living out of his car refuses to sacrifice his artistic vision by selling the rights to his script. He ultimately makes it big. But, the Rocky movies are much, much more than sports movies. This is a hero epic, and we witness the full arc of the character: the boy from the streets making good and shaking of his ties to local hoodlums, falling in love and building a family, achieving fame and success, making the mistakes of the nouveau riche, and suffering loss. Those who think his hardest fights are in the ring have missed the bigger story: Rocky’s incredible doggedness as a fighter is illustrative of the more important things he has to overcome, including his wife’s death by cancer, the passing of friends, estrangement from his son, the limitations of aging, and, ultimately, his own bout with cancer. Rocky IV takes place at the heart of the Cold War, opening in theatres at the same time as voting for the re-election of Ronald Reagan. The basic storyline is a challenge from the Soviet Union’s rising boxing star, Ivan Drago, to come to the West and crush America’s boxing champions. We see that Drago, stoically played by Dolph Lungren, is controlled, injected with steroids, and drilled mercilessly by his Soviet handlers. Over the course of the movie, we, the audience, develop a bit of pity for this individual who is just a propaganda tool for his Soviet overlords. Two themes emerge. The first is a private theme, discussed by Rocky, his wife, and his friend Apollo Creed. That is the question, “When is enough, enough?” and it is tied to an individual’s decisions about what one values in life. Creed is unwilling to face his own declining powers, lusting for glory in the limelight. Rocky argues that they are just men, facing realities of time and age. Moreover, Rocky emphasizes that family and relationships are the most important things to him. In some ways this debate is symbolic of a larger theme in the movie, whether the massive, mechanistic Soviet Union will overcome an aging, divided America. The geo-politics of sports rivalry goes all the way back to the 1936 Olympics, when Hitler’s regime staged the games as a Hollywood drama. Of course, despite the propagandistic images and truly massive venues, the Nazis were unable to prove their doctrine of Aryan supremacy on the racetrack due to the likes of Jesse Owens. After World War II, the geo-politics of sports centered on the Cold War rivalry between the free West and the Communist East, including everything from individual athletic drama to boycotts. In point of fact, the two systems were quite different. The Olympiad was designed for amateur athletes, so those in the West typically had only modest sponsorships available to them. In the East, Communist governments asserted control on every aspect of life, and that included taking children from their families at a young age and developing them as athletes. Looking back, we recall the national pride in competition by some of those athletes: Bruce Jenner (USA) shattering the decathlon record and fourteen year old Nadia Comaneci’s perfect “10s” (Romania) in the 1976 Summer Olympics; the 1980 ‘Miracle on Ice’ (U.S. hockey beats the Soviet Union); the ice skating duel between East Germany’s Katerina Witt and America’s Debi Thomas (1988), when both skaters performed to Bizet’s Carmen. Rocky IV captures the difference in these societal systems. In the Soviet Union, Ivan Drago is in essence a minion of the state. The massive resources of the Soviet machinery are brought to bear, and in typical ‘scientific’ Marxist fashion, Drago’s coaches and handlers brag about the novel techniques they employ to enhance and perfect human performance. This is not just propagandistic drivel. Rather, this reminds us that the anthropology of communism is entirely materialistic, and the elites of communism have always egotistically believed they can shape human nature itself. Rocky Balboa, on the other hand, is a private citizen. The fight that will occur is not sanctioned by a world boxing association. Rocky receives no support from government, media, or corporate sponsors. Rocky is fueled by a need to vindicate the loss of his friend, Apollo Creed. The soundtrack captures the sentiment in Hearts on Fire: “burning with determination to even up the score.” We see that he is at his very strongest when supported by his wife and close friends. Before the landmark fight in Moscow, we see him kneeling in silent prayer. In sum, the communists’ motivation is their never-ending need to justify their horrific, repressive regime. Whether at the Olympics, or in the fictional tale of Ivan Drago, that is what is going on. We continue to see it today, such as China’s recent massive military parade celebrating not just the end of World War II, but their new aggressive claims of primacy on the world stage. We see it in the grotesque grandstanding of North Korea, which starves its people to pay for massive statues of the Kim family and unnecessarily massive military industrial complex. How does America justify its fundamental ethos? By the success of its individuals under conditions of ordered liberty, the innovation and growth caused by free markets, and the resilience and accountability of our democratic institutions. Rocky Balboa is a fictional character whose grandparents probably came from Italy to Ellis Island and then to Philadelphia’s south side. His is a fictional version of the American Dream, but one lived by countless millions of others. In the final minutes of the fight, Rocky’s incredible resilience in rising up again and again from the floor, and his unbelievable determination despite Drago’s hammering blows, has turned the crowd in his favor. What began as a bloodthirsty crowd chanting “Drago” has become a frenzied audience yelling, “Rocky! Rocky! Rocky!” Rocky wins. But, Rocky IV is not through teaching us. Had Drago won, the Soviet Union would have crowed its superiority. In contrast, a battered Rocky is magnanimous. Taking the microphone, he exhaustedly addresses the crowd, I came here tonight and I didn’t know what to expect. I’ve seen a lot of people hating me, and I didn’t know what to feel about that, so I guess I didn’t like it much …During this fight, I seen a lot of changing. The way yous felt about me, and the way I felt about you. In here there were 2 guys killin’ each other, but I guess that’s better than 20 million. What I’m trying to say is if I can change … and you can change … everybody can change. Ronald Reagan characterized the Rocky mindset. Reagan struggled against an evil empire while always seeking ways to build bridges to subject peoples held captive behind the Iron Curtain. Reagan’s successor, George H.W. Bush, worked hard to demonstrate a “change” that allowed for Warsaw Pact countries such as Poland, Hungary, and the Baltic States to integrate into Europe and NATO. The side that wins does not just do so through the power of the state and its military, but by the persuasiveness and reality of its fundamental values. The power of the Rocky myth is that it expansively expresses the American Dream, for ourselves and for the world

- Deportation as Class Strategyby Oliver Eagleton on September 30, 2025

By making immigration the defining issue of the 2024 election, Donald Trump simultaneously created two political liabilities for his incoming administration. First, it was unclear whether he could fulfill his promise to launch the “largest deportation operation in American history,” vowing to expel at least a million people each year while “sealing the border” through

- Syria’s Future After the Massacre in Sweidaby Malek Rasamny on September 29, 2025

On July 15, the armed forces commanded by Syria’s transitional government, under the presidency of former rebel leader Ahmed al-Sharaa, were sent into the Druze-majority province of Sweida. The supposed aim was to restore calm after clashes between local Druze and Bedouin populations in the region. What ensued was a massacre that has strained the

- Go See One Battle After Another Right Nowby Eileen Jones on September 29, 2025

Glory be, I really liked and admired Paul Thomas Anderson’s One Battle After Another. It’s enthralling, it’s hard-hitting, it’s up-to-the-minute in its topicality, it’s drawing on and doing full justice to a multitude of genres including action, comedy, suspense, and the political thriller — plus it’s got a mesmerizing, undulating, hill-and-valley climactic car-chase scene like

- Zohran Mamdani’s Golden Opportunityby Corey Robin on September 29, 2025

Reading this New York Times report on Eric Adams’s dropping out of the race — where Adams is described, with no sense of irony, as “politically moderate” and is quoted as warning against Zohran Mamdani’s desire to “destroy the very system we built together over generations” while Andrew Cuomo is quoted as saying, “We are

- What the Giving Pledge Really Gave Usby David Moscrop on September 29, 2025

In 2010, billionaires Warren Buffet, Bill Gates, and Melinda Gates launched The Giving Pledge. The idea was that the world’s wealthiest ought to give back to the world, so signatories promised to donate half their wealth. Over the years, the Pledge steadily collected new members, reaching more than 250 donors including Elon Musk (2012), Larry

- On Free Speech, Jacobin Has Always Been Consistentby Branko Marcetic on September 29, 2025

Ever since Donald Trump launched a wide-ranging assault on free speech and the First Amendment last week, the Internet and airwaves have lit up with charges that one or another side are being hypocrites. Trump loyalists point to Democratic officials’ and high-profile liberals’ earlier support for restricting speech in various arenas, while those same left-leaning

- France Is Deep in Debt but Failing to Tax the Superrichby Michele Barbero on September 29, 2025

As France wonders if its new prime minister, Sébastien Lecornu, can cobble together a government coalition and squeeze through next year’s budget, debate is raging over soaring economic inequality — and the tax system that’s contributing to it. Lecornu’s predecessor, François Bayrou, was toppled in September over a series of belt-tightening proposals widely accused of

- Zelensky Does Indeed Have ‘Cards’—But Can He Negotiate with Trump?by James Diddams on September 29, 2025

As the Russia-Ukraine War continues its attritional stalemate, the Korean War armistice has sometimes been presented as a model for the eventual war settlement. Ukraine has initially rejected comparison to the Korean War, advocating instead for a successful counteroffensive to expel Russian aggression. Today, with the diminished prospects for regaining its lost territories through military means, Ukraine’s proposed terms are similar to those of the Korean War armistice: a ceasefire line without formal recognition of Russia’s territorial occupation, robust security reassurance from the West to deter Russia’s future aggression. Ukraine, however, faces challenges in achieving a Korean War-style settlement. Russia has continued its military offensive in pursuit of its maximalist aims. The Trump administration has opposed Ukraine’s NATO membership and is unlikely to offer a formal bilateral defense pact similar to the US-South Korea mutual defense treaty. The Trump administration has also displayed reluctance to provide military aid or deploy troops to support Ukraine’s post-war security. Ukraine continues to be threatened by the prospect that the Trump administration, impatient for a quick war settlement, would concede to most of Russia’s demands, pressuring Ukraine to either accept an adverse war settlement or risk US abandonment. During the Korean War armistice talks, South Korean President Syngman Rhee used two bargaining “cards” to achieve security reassurances from the US Eisenhower administration. Rhee’s first card was the US containment strategy. US policymakers considered the Korean Peninsula as one of the early tests of the containment strategy to deter communist expansion in the Asia-Pacific. Threatening to persist in his hardline stance that risked South Korea’s abandonment, but could also result in a defeat of the US containment strategy, Rhee imposed strategic burdens on US policymakers. With US forces fighting in Korea under the multinational UN Command, South Korea’s fall to communism was also perceived as forfeiting US military sacrifices in Korea. Rhee’s second card was the POW exchanges between the UN Command and the communist forces. Rhee threatened (and eventually implemented) to release unilaterally North Korean prisoners who refused repatriation. The US policymakers feared Rhee’s POW release could result in the suspension of the armistice talks and jeopardize the release of US prisoners kept by communists. Weighing the alternatives of either removing Rhee from power or placating him with more reassurances, the Eisenhower administration chose the latter, calculating that keeping a stable, cooperative South Korean regime would be more beneficial to maintaining geostrategic balance in the Korean Peninsula (to mitigate risks of Rhee’s militant actions, the US kept operational control of South Korean military as a condition for mutual defense pact). Ukraine’s president, Volodymyr Zelensky, lacks similar bargaining leverage in his negotiations with the Trump administration. The US troops are not fighting in Ukraine, reducing the US policymakers’ burden to avoid a perception of military defeat (a dilemma that contributed to prolonged US military intervention in Korea, Vietnam, and Afghanistan). As the Trump administration’s strategy is to reduce US security commitment abroad, emphasizing Ukraine’s vulnerability could backfire, reinforcing Trump’s aversion to costly intervention in the Russia-Ukraine conflict. Zelensky, however, has alternative bargaining cards. The first card is Ukraine’s military capability. Militarily unprepared for North Korea’s invasion, South Korea nearly fell before the arrival of the UN Command repulsed the North Korean forces mostly back to the pre-war border. Though the South Korean military eventually performed proactive roles in maintaining the battlefront, it remained militarily dependent on the UN Command. In contrast, Ukraine’s military successfully defended its capital, Kyiv, during the early days of the war. While the West refrained from direct military involvement (supporting Ukraine mainly through military aid, intelligence support, and economic sanctions on Russia), Ukraine’s military generally maintained resilient defenses against Russia’s continued offensives and has enhanced its domestic military capability as the war progressed. Zelensky’s second card is his partnership with neighboring European countries. Rhee’s South Korea had no reliable ally other than the United States. Due to South Korea’s history of colonization by Japan, Rhee rejected the possibility of a security alliance with the latter. Though European countries contributed troops to the UN Command, concerns that a prolonged war in East Asia could weaken US security commitment in Europe motivated their support for an armistice. Subsequently, Rhee distrusted multilateral security guarantees involving Europe, pursuing instead a bilateral pact with the United States. In contrast, many European governments have perceived the Russia-Ukraine War as posing a mutual threat to Europe’s security. Multiple European leaders have continued to affirm their diplomatic solidarity with Ukraine, urging the Trump administration to protect Ukraine’s security interests in the prospective Russia-Ukraine War settlement. The Trump administration’s threat to reduce US involvement in Europe’s collective security has incentivized increased attempts by European governments to expand their military capability. European governments have also endeavored to provide solutions for the Trump administration’s reluctance to continue direct aid to Ukraine. For example, France and the UK have proposed deploying European peacekeepers to maintain the future peace agreement between Russia and Ukraine. As well as continuing to send their aid to Ukraine, European countries have also explored arrangements in which they could pay for the continued delivery of US arms to Ukraine. Zelensky’s third card is Ukraine’s economic resources. South Korea, lacking substantive natural resources and its economy devastated by the war, had little post-war economic value to offer the United States. Ukraine, geographically the largest country in Europe (excluding Russia), has extensive agricultural and industrial capacity that has remained intact despite the destruction from the war. Ukraine’s rare earth resources have also led to the signing of the bilateral mineral resources agreement with the Trump administration. With these cards, Zelensky can engage in a different bargaining strategy. Rhee’s brinkmanship diplomacy paid off in persuading the Eisenhower administration to expand security commitment in the Korean Peninsula. Zelensky could instead engage in transactional diplomacy that mitigates the Trump administration’s wariness toward the cost of supporting Ukraine. Emphasizing Ukraine’s military capability and Europe’s cooperation, Zelensky could bargain for limited, “manageable” US security contributions (such as arms export to Ukraine, sanctions on Russia). US support would be reciprocated by promises of benefits from Ukraine’s economic recovery and development of mineral resources. Through mitigating the cost of support and promoting the returned benefits, Zelensky could be successful in unlocking Trump’s endorsement of a war settlement that is closer to Ukraine’s preferred terms. Zelensky’s cards have limitations. The prolonged war has inflicted substantive losses on Ukraine’s society and military. Ukraine struggles with a shortage of troops, and its domestic military capability is not yet sufficient to fill the gaps that would result from the suspension of the US military support. The expansion of European military capacity will likely take time, constraining Europe’s capacity to support Ukraine. Ukraine’s economic opportunities may be undercut by the difficulty in implementing its economic development while the conflict with Russia continues. Subsequently, Ukraine’s path to a negotiated war settlement is riddled with risks and challenges. Zelensky’s advantage, however, may be that his cards are more appropriate in bargaining with the Trump administration. While Rhee’s bargaining strategy relied on a threat, “United States must provide more support or else will lose South Korea”, Zelensky’s strategy can be based more on reassurance, “United States only needs to help Ukraine and Europe just enough and will be rewarded.” It is the second strategy that is more likely to be successful with Trump’s “transactional” foreign policy. With Trump’s recent shift toward support for Ukraine, there’s an opportunity for Zelensky to bargain for a war settlement that could safeguard Ukraine’s security even with a more limited, transactional US security commitment.

- The GOP Is Refusing to Interrogate Trump’s Big Tech Alliesby Freddy Brewster on September 28, 2025

Republican lawmakers recently ordered social media companies to testify before the House Oversight Committee to “examine radicalization of online forum users, including incidents of open incitement to commit violent politically motivated acts” — while notably excluding companies led by Trump’s closest Big Tech allies. The hearing, scheduled for October 8, comes in the wake of

- The Evangelical Political Theology of Charlie Kirk’s Funeralby James Diddams on September 25, 2025

Charlie Kirk’s funeral this week in a packed professional football stadium in suburban Phoenix drew somewhere between 200,000 and 300,000, a TV viewership of tens of millions, the inevitable controversy that comes not only with the assassination of a prominent activist, and the more particular controversy that comes the public meetings that wed Christianity and politics. Few events in recent American political memory have combined politics and religion as openly, or as perhaps as seamlessly, as the funeral Turning Point USA provided ostensibly for the family and fans of Charlie Kirk. The event influenced political, religious, and social discourse in the United States, and there is no reason to believe the funeral will soon be forgotten. Affecting moments, from Evangelical cleric Frank Turek’s Christ-focused eulogy, to the sitting Secretary of State’s earnest declaration of the Christian Gospel, to the President of the United States’ cheerful but unabashed dismissal of the Christian command to love enemies, to most poignantly Erika Kirk’s public forgiveness of her husband’s killer, all became instant and striking soundbites and points of discussion for Americans who loved Charlie Kirk’s easy association of his faith with right wing politics. Those same memorable moments from Kirk’s funeral—captured on video for posterity—inflamed the opinions of Americans who fear a religious and particularly Christian takeover of the American state. The day after the funeral, CNN columnist Zachary B. Wolf wrote that while Americans were “used to hearing about the tradition of separating church and state, but the two are increasingly fused in President Donald Trump’s administration.” Never in recent memory, said Wolf, had “Americans seen more top government officials speak so openly about Jesus Christ as they did at Charlie Kirk’s memorial, which Trump described as ‘an old-time revival’ rather than a funeral.” Americans approach the relationship of religion and politics in various ways. Secularists believe that religion—usually Christianity—should be absented, even forcefully so, from politics. Others believe that religion, particularly religion rendered from the Abrahamic traditions, necessarily informs the American political order, and should therefore have a prominent rhetorical and intellectual place in the American political order. A very small rump of Roman Catholics and Protestants would subsume the state into an ecclesiastical order. Charlie Kirk’s funeral was not, it might be noted, run by a church, nor was the event even a funeral in a traditional sense. It was a public meeting, held by a company—TPUSA—that included clerics and politicians speaking to fans and devotees in their capacity as friends of Charlie Kirk. It was, in one sense, a private event. But therein lies the potential rub. Do the president—and vice president, and cabinet officers—actually speak in any public capacity as merely private citizens, and can religious speech or actions done with the associated presence (but not necessarily endorsement) of the United States’ federal government be merely incidental? These are important questions, largely because the answer is not readily clear. There are no clear constitutional precepts that Charlie Kirk’s funeral abrogated. No laws were broken; no one was oppressed for their religion or lack thereof. But there were customs that were abridged, and it is perhaps those customs, rather than federal laws or the Constitution, that need to be revisited in 2025. All of the United States’ presidents have identified as Christians, and a significant number of them have been actively pious. The same reality applies to the vice president, the cabinet, and congress. But throughout most of the American republic’s history, presidents maintained a customary aloofness from certain types of religious events, particularly events that might be seen as inappropriately uniting church and state, and events that might be deemed to be sectarian. Churchly funerals were avoided by presidents. During the longue duree of the 20th Century, Protestant churches filled more and more social and political space. A national cathedral was created, wherein the Episcopal Church was treated as a de-facto state church of the American Union. Mainline Protestants, whose increasingly syncretic theology saw little in the way of threats to the liberal order from churches, never worried about their syncretism. It was popular, and widely accepted. The decline of the Protestant mainline in the 1960s, and the balkanization of American society in the aftermath of the Cold War, meant that the old mainline syncretism of early and midcentury America could no longer assume widespread societal support. The rise of Evangelicals in particular meant that a new religious demographic increasingly ruled the roost of political religion especially in conservative circles. By 2025, Evangelicals outnumbered mainliners and represent the mainstream not merely of conservative Christianity, but of Protestant Christianity in general in the United States. They are generally conservative, and support Republican politics. Like their mainline cousins, they do not have a reflexive theology that separates politics from religion. Kirk’s funeral, far from being a deviation from the historic American mean, is evidence of a transfer of American religious syncretism from classically liberal mainliners to populist conservative Evangelicals. Politically conservative Evangelicals undoubtedly see this as a victory, but there is no reason to think that Evangelicals, like the mainliners, won’t lose their theological saltiness to a desire for political power in just the same way their mainline cousins did. Even now, Evangelicals are renegotiating long-standing beliefs in order to maintain their place at the Trumpian table. Perhaps this is what any politically influential group has to do. But there’s no reason to think that history has given Evangelicals clairvoyance that mainliners lacked. Evangelicals who concede this similarity and know about the historical consequences might be likely to be cautious in further mixing of politics and religion. The issue at present, however, is that too many Evangelicals think they won’t make the same mistakes as the mainline.

- Why we’re giving incarcerated women cash reliefby Andrea James on September 25, 2025

We’re the first project to give women in prison recurring cash support. Our long-term goal is prison abolition

- In Defense of Dark Humor by James Diddams on September 25, 2025

How could I have laughed at that? I remember being shocked at myself the first time that I heard a particularly dark joke during my time as a strategic communications officer for an intelligence agency. I worked at a center that specialized in media exploitation, where torture videos, disturbing proof-of-life footage, child pornography, and other terrible media content were regularly unearthed in captured ISIS, Al-Qaeda, and other terrorist electronic devices and media. The joke in question was made by the center’s former Hardware Exploitation Laboratory (HEL) manager, and, without relaying the exact particulars, it simultaneously made fun of Islamic Extremist terrorists’ proclivity for child marriage, pornography, and modern dating apps. It was appalling. And it was funny. Despite the punchline’s references to the evils of child marriage and pornography, I found it wickedly funny and—perhaps to assuage my own conscience—have been pondering the role of dark humor ever since. In a recent discussion, Lorraine Murphy, professor of English at Hillsdale College, described how all great stories, comedies and tragedies, demonstrate a “willingness to look at the darkness.” Truly memorable stories acknowledge the brokenness of our world and humanity’s immense capacity for evil. Humor, especially satire and dark humor, plays with the incongruence and deviation from how things are and how they ought to be. It highlights the absurdity of evil in ways plain English can’t. Likewise, my former coworker’s joke hit on an ugly truth, momentarily laying bare the evil that my colleagues and I dealt with every day. The crude joke mocked an evil that, except for rare moments, was compartmentalized and handled with detached professionalism. It dared to “look at the darkness” through the guise of levity. Throughout the Western literary tradition, humor has historically been a means of acknowledging the darkness present in the human condition, often by exposing moral failures and hypocrisies. In book 4 of the Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle argues that wit, when used correctly and not in excess, is a valuable tool in conversation. Erasmus, the father of humanism and key figure in the Renaissance, was able to critique the 16th century Western church and society by cloaking his less than flattering appraisals in humor in his highly entertaining essay In Praise of Folly. Consider also Shakespeare’s Fallstsaff, the embodiment of the clever court jester, poking fun at the absurdities and shortcomings of monarchs and court officials through cleverness and the entertaining quality of his wit. Humor has always had the unique capacity to make hard truths simultaneously more bearable and more potent. Dark humor is no different—it brings hard truths or hypocrisies to light in a way that is simultaneously more bearable (because, well, it’s funny!) and yet also unsettling (because of its grim subject matter), making whatever uncomfortable truth that the joke uncovers especially resonant. Winston Churchill exemplified such humor; throughout WWI and WWII, his sense of humor was never diminished but rather was sharpened through his gruff and courageous leadership style. For example, Churchill’s quip that “Americans will always do the right thing, after they’ve exhausted everything else” continues to spark laughter, decades after Churchill’s death, for its encapsulation of the ironic position of America as the savior of the free world. Abraham Lincoln also exemplified the value of dark humor in trying times. At a cabinet discussion of the Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln opened the meeting with a funny story from a favorite humorist of the time, Artemus Ward. Unsurprisingly, some members of his cabinet, including Lincoln’s Secretary of War, made known their disapproval, to which Lincoln responded, “Gentlemen…with the fearful strain that is upon me night and day, if I did not laugh I should die.” Dark humor, then, does more than merely acknowledge the darkness. As Lincoln reminded his cabinet, it acts as a medicine against despair, and, by uplifting spirits, can even be considered a form of resistance against the evil itself. After my former colleague told his joke, we grimly chuckled and stood there a moment, brooding over the unfortunate realities that made it so powerful yet appalling. In our professional environment, rife with terror and jihad, it was easy to grow numb to such evils. But instead, it was dark humor that kept us sane. My coworker’s joke rejected indifference and called attention to an issue in a way that resonated with those listening—a sort of camaraderie that broke down the emotional barriers we had erected against acknowledging the genuine horror of our work. Throughout the Western tradition and beyond, humor and sharp wit not only give art and voice to harsh truth, humor also—as anyone who has ever been the butt of a joke can attest to— cultivates a rebellious solidarity at the subject matter’s expense. Far from being disrespectful, the dark humor that prevailed in my former career in intelligence was a small act of resistance against the overwhelming, though often unacknowledged darkness. In fact, theologian Frederick Buechner, in his 1977 book Telling the Truth: The Gospel as Tragedy, Comedy, and Fairy Tale, goes so far as to argue that comedy is an agent of the Gospel, because the Bible and the story of man’s relationship with God can be considered both the ultimate tragedy and comedy—beautiful and absurd at the same time. He urges clergy to preach the gospel by embracing its tragic, comedic, and mythological aspects of Christianity. He closes his book with the following petition: “Let the preacher tell the truth…Let him preach this overwhelmingly tragedy by comedy, of darkness by light, of the ordinary by the extraordinary, as the tale that is too good not to be true, because to dismiss it as untrue is to dismiss along with it that catch of the breath, that beat and lifting of the heart near to or even accompanied by tears, which I believe is the deepest intuition of truth that we have.” Comedy is forever intertwined in mankind’s relationship to the Divine—an unavoidable part of the human experience and one of the deepest intuitions that we possess. And so, while dark humor is certainly not appropriate for every situation, we should remember that wit and humor need not be strangers to serious discourse. We often take ourselves too seriously in politics and international affairs, thereby depriving ourselves of the special potency with which humor can deliver an ugly truth or expose a hidden ill. As we encounter the darkness of this world and the absurdities that arise in the business of warfare, let’s not forget that humor offers a weapon of its own: a deterrent to pessimism and a herald of truth that reverberates within the deepest recesses of our humanity.

- How tech became the new frontier of domestic violence against women and girlsby Emma Pickering on September 24, 2025

The government will not meet its pledge to halve violence against women and girls unless it tackles tech companies

- Nuclear Weapons: A Game of Possession and Numbers by James Diddams on September 24, 2025

Imagine Adolf Hitler with an atomic bomb, or worse atomic bombs during World War Two. History would have taken a drastically different turn for the worse. It was this nightmarish scenario which in 1939 motivated Leo Szilard and Albert Einstein to write a letter to Franklin Roosevelt, urging the allies to develop a bomb before the Nazis. History took its own turn, the Nazis were defeated in May 1945, and three months later the bomb was used against the Japanese to end the war. Would that we could get rid of these apocalyptic atomic beasts once and for all, as many have wished, but since August 1945 further avoidance of their use is a game of possession and numbers. First, let us talk about numbers. Zero Atomic Bombs, Anywhere It is still a nice and very tempting dream, that we would like to make a reality. No nuclear bombs anywhere, translates to zero chance of a nuclear apocalypse, right? Let’s not leap to that conclusion so fast. The last time there were zero nuclear weapons anywhere takes us back to before July 1945 when the world was waging war. The Nazis had just been defeated, but the war with Japan still waged on. In fact, the whole history of humankind up to that point had been one of almost incessant warfare. If one nation were not invading another for land or gain, then it was just biding its time for the right opportunity. A realist understanding of human nature comprehends just how brutal our species can be to our own kind, in the blind interests of power and nationalism. It wasn’t even that way just in the twentieth century, but for a whole swath of history dating back to Genghis Khan, Alexander the Great, or Julius Caesar, just to name a few. Going back to the time when there were exactly zero bombs invites reigniting that civilizational boxing match, where the nations are not afraid to fight because they know they will not die. If there is one crazy “blessing” of the threat of nuclear war, one could argue it keeps great powers and nations in check because they know they cannot get away with what they used to. So going back to zero bombs just invites the anxiety of not knowing what sociopathic world leader might get a hold of them first. In Einstein’s day it was Hitler, but today it could be a terrorist group like Hamas, Isis or Al-Qaeda. Mutually Assured Destruction – that grim postulate that if one nuke is used, the whole of civilization may go up in a conflagration – still seems to be a controlling idea. The idea which keeps great powers in check and prevents us from pressing that forbidden trigger. There are perhaps 12,000 or 13,000 nuclear weapons in the world today. It is insanity for any nation possessing them to use them in expectation of making some gain. Still, it is not a comfortable idea, nor one that we should be complacent about. If there were fewer bomb systems, there might be less chance of one getting into the wrong hands. The more tantalizing nuclear fruit hanging out there, the more risk is engendered of a rogue plucking it. Nuclear theft, the stuff of movies, cannot wholly be ruled out. Just how many nuclear weapons should we possess, so that one does not get stolen, nor does it become conceivable to use them? That is a hard question to answer. It’s the game of numbers, which cannot fully be resolved here. What of the game of possession? Who Possesses Nuclear Weapons At least nine countries possess nuclear weapons: the Unites States, Russia, China, France, the United Kingdom, India, Pakistan, North Korea, and Israel. Not all of them respect nor honor the non-proliferation treaty of 1970, intended to keep the ownership of nukes from spreading. It is not just how many nukes there are that matters, but who has them. America does not worry about nuclear weapons from the UK, France, nor Israel, and probably not India or Pakistan either. But what of the threat of nukes coming from Russia, China, or North Korea? And what if Iran were to be added to this list? India’s nukes are of greatest concern to Pakistan, and vice versa. If Iran were added to the list, they would be the gravest threat to Israel. The family of world nations really isn’t a family, or if it is, it is a very dysfunctional one, where brothers and sisters still live with a venomous animosity. Who has the weapons, and what nation or nations they might be pointed at, is a crucial concern. It seems sometimes absurd that we build these things we never plan to use. But it is their existence, and simultaneously their non-use, which checks the greater human appetite for war. Putin has rattled the nuclear saber, but as long as he retains some common sense, he will not draw it. Since August 1945, thankfully, no further use of nuclear weapons has taken place. How do we keep it that way? It is at least a game of numbers and possession. Keeping a certain number of weapons on hand, so that their use is not tempting, and trying to ally and unite their possessors as much as possible seem to be good ideas. If there were no ideological nor power splits between the nine nuclear powers, the threat would be further lifted, but we know the rifts are real and significant. Realism is taking stock of the fundamental factors of our life. Nuclear realism realizes that part of this seems to be an inevitable game of numbers and possession. Would that we could go back to a time when no countries possessed nuclear weapons. That is an understandable dream. But is it realistic?

- Reparations for racial injustice: Black fathers must be first in lineby Kamm Howard on September 23, 2025

Racial inequities mean Black kids increasingly grow up without fathers in the US. Reparations could break the cycle

- International Courts and Military Action: Clarifying the Distinctive Ways of Protecting Human Rights by James Diddams on September 23, 2025

In our increasingly divided societies, the possible meanings of politically relevant words are also divided, confused, and obfuscated. Though the competition for the most contested words is intense—’fascism,’ ‘democracy’ and ‘liberal’ are surely near the top of the list—’rights’ is surely a contender, used in many different, confusing, and contradictory ways. One confusion is between rights that are legally recognized by a political order, such as a bill or charter of rights, and those that are part of a transcendent moral order. These latter are commonly called innate rights, subjective rights, or natural rights. They are held to be inherent, already given, rights that should therefore be recognized in positive law by any state with pretensions to a just political order. The origin of theories of these latter rights is now generally held to have been in 11th and 12th century canon law. The ways in which natural rights might properly be protected in diverse political orders will necessarily vary. One can be a fervent believer in natural rights while also recognizing that the ways in which they should be protected will properly vary. THE AMERICAN EXAMPLE Two famous interconnected expressions of these different meanings of rights are the American Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. The Declaration famously declares that rights come from our Creator: “all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness….” (We might here note Senator and former Vice-Presidential candidate Tim Kaine’s hapless contention that believing that rights come from God not the government is specifically typical of regimes such as Iran.) Despite this clarion declaration of natural rights, most original drafters of the Constitution did not seek to provide any a bill of rights. This was not because they did not believe in such rights, but for two reasons: One was a fear that if certain rights were enumerated in the text, then any unenumerated rights, while also reflecting natural rights, would be left open to government abuse. Another was that they thought that the constitutional arrangements that they had already provided—the constitutional order itself, democratic elections, division of powers, and federalism—were themselves sufficient to protect rights. However, to gain the support of those concerned that the Constitution still did not give sufficient protection to rights, amendments were introduced, the first ten of which we now call the Bill of Rights. Note that these are amendments, later added protections to overcome the concern that the original did not sufficiently protect rights. UK CONCERNS Similar concerns have recently arisen in the United Kingdom over whether the country should continue to be under the jurisdiction of the European Court of Human Rights. The UK is currently attempting to stem a massive influx of people arriving in small boats across the English Channel. When the country was part of the European Union, it could deal with this as an EU matter but, after Brexit, that option is closed. But, while no longer part of the EU, it is still a party to the distinct European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), and many claim that the Court’s expansive rulings are unduly restricting the UK’s ability to properly control such immigration. Consequently, there is a push for the UK to leave the ECHR, and this has produced a strong reaction. One human leading rights lawyer argued that leaving the ECHR would align the UK with countries like Belarus and Russia, “neither is a democracy nor uphold the rule of law.” He added that if it left the ECHR, “The UK would lose all moral authority to promote and protect human rights globally.” But this confuses substantive protection of human rights with adherence to a particular legal mechanism for such protection. Not being a member of the ECHR would of course put the UK in the same camp as non-members Belarus and Russia. But the same camp of non-members also includes the US, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Japan, and most of the world’s countries, free and unfree. Here I take no position whether adherence to the ECHR has deleterious effects on UK immigration or any other policy, nor whether UK withdrawal from the ECHR would be a net loss. I simply want to clarify that there are many mechanisms to protect human rights and that international courts and charters are only some of them and may not always be the best mechanism. Currently, protection of human rights in the Ukraine depends more on the bravery and ingenuity of its soldiers together with weapons shipments from the West than it does from any court. RHODES’ ANALYSIS Aaron Rhodes excellent new book, Human Rights Without Illusions: Escaping the Moral Trap of Universalism analyses these issues in more depth and stresses the very varied ways in which human rights can be protected.1 He brings a rare set of academic, analytic, and above all, practical and advocacy skills in the international arena. He has fought for these matters for many decades and here concludes that abstract international rules and courts, especially with their lack of any enforcement mechanisms, make them aspirations rather than laws, and count for much less than actions by states. Rhodes can be misleading in his history, suggesting that developed rights ideas first appeared in the seventeenth century rather than the medieval period, but his strength is as a philosophically informed, long-term activist, and political realist drawing on a wealth of experience in unravelling and analyzing current views of rights and their results. He especially highlights the chasm between abstract human rights ideals and their often-disappointing global realities. Rhodes argues that the common current framework of international human rights, stressing western law and courts, can lead to a moral imperialism that undermines the true intentions of these rights. The Trump administration’s critiques of the ‘woke’ assumptions of some previous USAID programs, while exaggerated, shows that such fears have not been illusory. He is wary of overreach and stresses the complexities of sovereignty, governance, and human agency. In response to abstract legal universalism, Rhodes suggests a more pragmatic, locally adaptive approach to human rights that encourages accountability while respecting national sovereignty. One that is state centered rather than simply relying on international fora lacking substantial enforcement mechanisms. To vastly oversimplify matters: if you are caught in a vicious conflict in Africa, what would most rejoice your heart to hear were coming: a group of prosecutors or else an armed brigade? The book’s clarity and depth make it essential reading for scholars, policymakers, and anyone interested in the future of human rights in an increasingly multipolar world. Rhodes’ criticism of contemporary human rights approaches parallels Mark Amstutz’ excellent critique in these pages of Ken Roth’s Righting Wrongs: Three Decades on the Front Lines Battling Abusive Governments, https://providencemag.com/2025/07/can-advocacy-organizations-and-international-courts-advance-human-rights/. See also https://providencemag.com/2025/06/why-nations-and-national-self-interest-are-the-building-blocks-of-international-order/ ↩︎

- Capital Crimes and Punishment: The Matter of Justice by James Diddams on September 22, 2025

As I write news is arriving of the fatal shooting of the conservative activist Charlie Kirk on the campus of Utah Valley University in Orem. This come only hours after I read of the fatal stabbing on September 6 of a retired Auburn University professor who was walking her dog in a local park in Auburn, AL, then forced into the woods and stabbed multiple times. Also in the news this week are ongoing reports of another fatal stabbing – this one in Charlotte, NC, and of all places, in a light rail train. The murder was committed by a repeat offender (according to reports, some 14 arrests and releases) who faces federal murder charges (given that it happened in a mass transit system). The victim happened to be a 23-year-old Ukrainian refugee who came to the U.S with her mother, sister and brother to escape the war in Ukraine. We are still reeling, of course, from the mayhem and mass shootings that occurred only two weeks ago. On the morning of August 27, in southwestern Minneapolis a gunman armed with a semi-automatic, a 12-gauge shotgun, and a pistol stormed his way into the Church of the Annunciation during a scheduled school-wide Mass that was attended by students and faculty of Annunciation Catholic School, killing two and injuring eighteen. (Perhaps we have already forgotten the attempt at mass murder, barely two years ago, at the Covenant School, a Presbyterian Church in America elementary school in a southwestern neighborhood of Nashville, TN, where a gunman, a 28-year-old transgender man and former student, killed three nineyearold children and three adults before being shot and killed by Metro Nashville Police.) And it was barely a month ago (August 11), that three people in Austin, TX, were murdered in a Target parking lot. This occurred just days after a quadruple murder in Jackson, TN, where authorities found an abandoned baby. The suspect was charged with the murder of the child’s parents, grandmother, and uncle. This depressing litany of murder and mayhem could go on and on. Not surprisingly, in late 2022 the Marshall Project reported that the last five years had been witness to more mass murders (four or more people) than any half-decade since the mid-1960s. Yet despite the incidence of violent crime around us, there exists in Western culture a strange reticence (unwillingness?) to acknowledge – much less debate – the character and demands of justice, properly perceived. Why is that? Justice, classically understood, is rendering to each what is due. One need not espouse Christian faith to acknowledge this moral principle; it is basic to “civil society.” Tragically, the foundations of law – namely, its theological and moral underpinnings – are dying (if not dead) in Western culture. America’s public philosophy of choice is rooted in a militantly secular and utilitarian view of law – a development that has been underway for several generations. Justice, however, depends on something beyond itself, if indeed it is truly “just” and therefore applicable to all in a universal sense. Justice requires a foundation of transcendent moral truth. Law, it needs emphasizing, is inherently “religious” in nature, regardless of whether it is acknowledged as such. When law loses what only a conviction of ultimacy can bestow, it degenerates into an inhumane utilitarianism with the consequence that moral-cultural breakdown ensues. Totalitarian societies, which are on the increase, are the end result of this process. It is supremely difficult for contemporary culture to acknowledge the reality of evil and the fact that it is part of the human condition that people do evil things to fellow human beings. It is hoped, rather, that preemptive strategies facilitated by brain research, genetic testing or psychosociopharmacology might alter in the some way the tendency toward deviant behavior. These attempts, alas, only render us less human and in the end foster greater social excuse-making. The question that confronts “civil society,” however, is the moral question. What will we tolerate? And will we tolerate those who murder in cold blood? Can “civil society” as we know it remain “civil” and “just” if we cannot affirm the sanctity of human life? In the case of murder, that is, the willful taking of innocent human life, we are confronted with values of the highest order. Capital punishment is one of those recurring issues that simply will not go away. Curiously, regarding the death penalty there is no “sacred-versus-secular” divide; most people in Western societies, whether they are religious or not, are abolitionist in sentiment, and overwhelmingly so. Traditionally, in the wider Western cultural tradition, punishment has been understood to be retributive, corrective or rehabilitative, and deterrent in character. Fundamentally, punishment is not just if it is void of the retributive element. After all, as a society we cannot inflict punishment on a person if he or she does not deserve it. Ask any parent. Just punishment must always be proportionate to the offense, particularly in the case of murder, a capital crime.1 In the present cultural climate, we are unable to answer the question of what is truly just in a “worst case” scenario (say, for a cold-blooded mass-murderer and rapist). In the case of premeditated murder, however, authentic justice does not impose a “life sentence,” or multiple “life sentences.” Such conceptions are simply incoherent, not based on any moral principle, and hence unjust. Having done criminal justice research in Washington, DC, prior to the university classroom, I write as one who has been wrestling with issues of justice much of my life. And even when the focus of that research over the years has shifted from domestic- to foreign-policy issues, I retain the conviction that the character of justice remains the same, whether applied to domestic or foreign policy. Inasmuch as justice must be the same for Kansans, Californians, and Coloradans, it must also be the same for Kenyans, Canadians, and Kazakhstanis. For this reason, we may glean important insights into the nature of justice by examining the primary moral criteria that comprise the “just war” tradition as classically understood in the wider Western cultural heritage. The tradition of “just war” (more accurately, “justified war”) is anchored in the primary moral conditions of just cause, legitimate authority, right intention, discrimination, and proportionality. Together they (a) justify whether or not to intervene coercively (ius ad bellum) and (b) justify the means by which coercive intervention is executed (ius in bello). At bottom, just cause, right intention, and proportionality mirror the very heart of justice. Just cause informs the need for coercive intervention based on fundamental moral distinctions – between innocence and guilt, between the criminal and the punitive act, between retribution and revenge, between “crimes against humanity” and humanitarian protection. For a response – for example, punishing evil – to be just, it must accord with human nature and moral accountability (doing good and resisting evil) and be proportionate to the injustice itself. Right intention governs the motivation of coercive intervention (or punishment) in the case of responding to evil. Coercive, even lethal, force can be “rightly” motivated for both positive and negative reasons; that is, it expresses charity, which desires the best for individuals as well as the common good (or peace) of societies, while it “dignifies” human beings by holding them accountable for their actions (what all parents intuit). Proportionality well expresses the very essence of justice, for it requires that we assess human behavior – in this case, criminal behavior – on the basis of merit and desert. We neither assign draconian penalties to petty misbehaviors nor slap the wrists of murderers and rapists. Punishment must always be proportionate to the crime committed. Contemporary culture is awash in excuses for not punishing proportionately. As it concerns the death penalty, such rationales are shared by secular and religious people alike. They include but are not limited to: (1) the fallibility of the criminal justice system, (2) the possibility of executing innocent people, (3) the purportedly capricious manner by which individuals are selected for execution, (4) purported racism, (5) a purported lack of statistical verification of deterrence, (6) the insufficiency of revenge as a motive, (7) a purported Eighth Amendment immunity, (8) Jesus’ supposed abrogation of the lex talionis in the “Sermon on the Mount,” and (9) the annulment of the Old Testament Mosaic code. The rationale for the Church’s historic affirmation of the death penalty – and the historic Christian tradition shows a clear acknowledgement thereof – is lodged in Scripture’s teaching on the sanctity and dignity of human life and in the natural law, as mirrored inter alia in Genesis 9:6: “Whoever sheds the blood of man, by man shall his blood be shed; for in the image of God has God made man.” This prohibition informs the Sixth Commandment: “You shall not murder” (Exo. 20:13). Note what undergirds these two divine commands: the prohibition is not in spite of human dignity but because of it. Because of the imago Dei, murder is the equivalent of effacing God himself, and thus worthy of losing one’s life. What’s more, the “philosophical” rationale for this is not mere revenge; it is rather to guard and protect innocent life from unjust invasions. In the public debate over the death penalty, we are dealing with values of the highest order, namely, respect for the sacredness and protection of human life. This expresses what Augustine called the tranquillitas ordinis in society, wherein people might flourish by means of a justly-ordered peace. At bottom, what is intrinsically wrong is not the killing of a human person but the intentional killing of an innocent person, as the “cities of refuge” in the Old Testament well demonstrate (Numbers 35, Deuteronomy 19, and Joshua 20). Does capital punishment in the case of convicted murder constitute an “uncivilized” societal response, as abolitionists maintain? The answer depends fundamentally on how we as a society understand the morality of crime and punishment. A society unwilling to impose the death penalty on those who murder in cold blood is a society that has abandoned its responsibility to uphold the sanctity of human life. In the end, civilized culture will not tolerate murder; an uncivilized one, however, will.2 A clear and concise argument for the centrality of proportionality in punishment can be found in Edward Feser, “In Defense of Capital Punishment,” Public Discourse (September 29, 2011), accessible at www.thepublicdiscourse.com/2011/09/4033/. ↩︎Elsewhere I examine the ethics of capital punishment variously; see, for example, “Outrageous Atrocity or Moral Imperative? The Ethics of Capital Punishment,” Studies in Christian Ethics 6, no. 2 (1993) 1-14; “Lethal Rejection,” Touchstone (Sept./Oct. 2016): 30-36; and “Capital Crimes and Capital Punishment,” Public Discourse (March 14, 2023), accessible at www.thepublicdiscourse.com/2023/03/88117/. ↩︎

- Israel’s growing pariah status is Gaza’s best hope after UN confirms genocideby Paul Rogers on September 19, 2025

Netanyahu’s finance minister this week described the development opportunities in Gaza as a ‘bonanza’ for Israel

- Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Nepal: Is This A South Asia Spring? | With Roman Gautamby Aman Sethi, In Solidarity Podcast on September 19, 2025

The protests in Nepal bear parallels to similar uprisings in Sri Lanka in 2022 and Bangladesh last year. On this episode, journalists Roman Gautam and Aman Sethi discuss if we are witnessing a South Asian version of the Arab Spring.

- Tolkien, Technology, and Geopolitics by James Diddams on September 19, 2025